Bitter Fruit: Marshall McLuhan and the Rise of Fake News.

Majin, G. (2022) Bitter Fruit: Marshall McLuhan and the Rise of Fake News. Quillette. 18 January 2022.

In Orson Welles’s classic movie Citizen Kane, the eponymous hero publishes a statement of principles on the front page of his newspaper, “I’ll provide the people of this city with a daily paper that will tell all the news honestly. … They’re going to get the truth from the Enquirer, quickly and simply and entertainingly and no special interests are going to be allowed to interfere with that truth.” It is a promise that Kane, a character loosely based on the press baron William Randolph Hearst, ultimately breaks. Today, the point Welles was trying to make is easily misunderstood. The movie is not being cynical about journalism, nor about the goal of searching for truth. Kane’s tragedy is that he falls short of his noble ideals. The movie was therefore acknowledging the contract that existed between journalists and their audiences during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was the expectation that journalists ought to search for, and report, the truth.

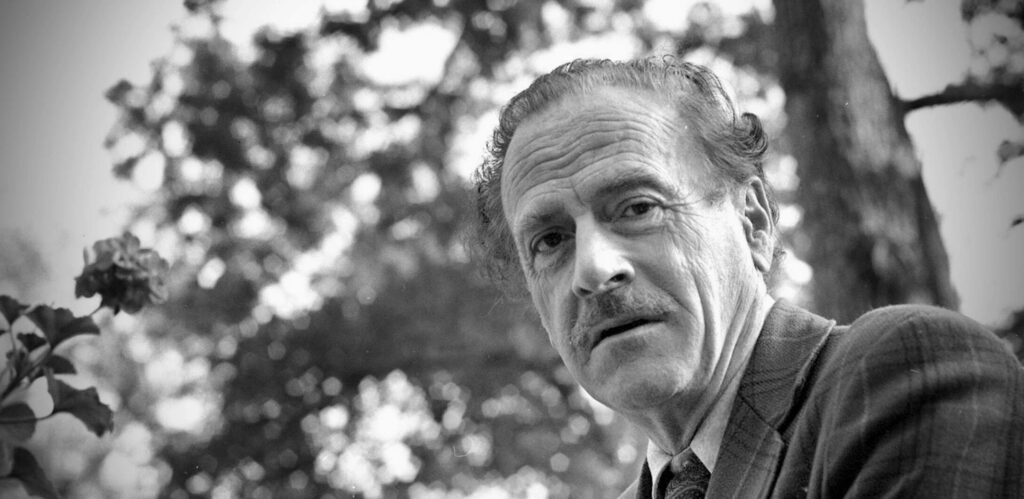

We have travelled a long way since then. The media ecosystem of the early 21st century is marked by a collapse of trust in journalism. How did we get here? As we look back, like a detective searching for clues, one moment stands out as significant; the publication on March 1st, 1962, of The Gutenberg Galaxy, written by a then-obscure Canadian academic named Marshall McLuhan. This book set in motion a line of falling dominoes, the consequences of which continue to affect us profoundly today.

McLuhan came to be regarded by the Baby Boomer generation as a guru and prophet; a visionary who had discovered something profound, not merely about the media, but about life and the universe. During the 1960s, he became a major celebrity, especially in the US. He featured on the cover of Newsweek magazine, was frequently interviewed on TV, and made a cameo appearance in Woody Allen’s 1977 movie Annie Hall. There was even a prog rock band named in his honor. The American media historian Aniko Bodroghkozy writes that “no other figure who was not of the movement itself received so much positive notice in the alternative newspapers that served dissident youth communities.” In 1965, the celebrity journalist Tom Wolfe asked breathlessly, “Suppose he is what he sounds like, the most important thinker since Newton, Darwin, Freud, Einstein, Pavlov?” Wolfe described McLuhan as an almost Christ-like figure:

A lot of McLuhanites have started speaking of him as a prophet. It is only partly his visions of the future. It is more his extraordinary attitude, his demeanor, his qualities of monomania, of mission. He doesn’t debate other scholars, much less TV executives. He is not competing for status; he is alone on a vast unseen terrain, the walker through walls, the X-ray eye.

A catastrophic media failure? Russiagate, Trump and the illusion of truth: The dangers of innuendo and narrative repetition.

Majin, G. (2019) ‘A catastrophic media failure? Russiagate, Trump and the illusion of truth: The dangers of innuendo and narrative repetition’, Journalism. doi: 10.1177/1464884919878007.

Abstract

The journalistic coverage of Russiagate, between 2017 and March 2019, has been described as ‘a catastrophic media failure’. Drawing on political and social psychology, this article seeks to enrich, and refresh, the familiar journalistic concepts of agenda-setting, framing and priming by combining them under the heading of the ‘news narrative’. Using this interdisciplinary approach to media effects theory, Russiagate is considered in terms of the Illusory Truth Effect and the Innuendo Effect. These effects hypothesise that the more audiences are exposed to information, the more likely they are to believe it – even when they are told that the information is unreliable. As a specific example, we focus on the stance taken by BBC News – which has an obligation to journalistic impartiality. We ask what implications arise from this analysis with regard to audience trust.

Keywords Agenda-setting, BBC, fake news, framing, illusory truth effect, innuendo, media effects, news narrative, priming, pseudo-facts, psychology, Russiagate, Trump

Published in the British Journalism Review. Volume 30, Number 1, 2019

A Brick Through the Window. How Auntie Responds to Scholarly Criticism in the Age of Tribalism.

They spent hundreds of hours honing their methodology, gathering their source material, categorising, analysing, evaluating and finally drawing their conclusions. The result of their labour, published earlier this year, measured the proportion of news broadcast by BBC 5 Live. The report, by Tim Luckhurst, Ben Cocking and their colleagues at the University of Kent’s Centre for Journalism Studies, clocked it at 45%. This is somewhat less than the 75% required by Ofcom.

The report’s 44 pages of detailed investigation pointed out that the corporation was reluctant to define news. It accused 5 Live of blending sport with news, and passing off the former as the latter. News UK, which owns talkRADIO and talkSPORT, funded the research, and must have been mightily relieved at the findings, which confirmed what they had long suspected.

If Luckhurst et al thought they were inviting the BBC to partake in a reasoned, scholarly debate about the definition of news, they were in for a surprise. The reply from the corporation was the intellectual equivalent of a brick through the window. A spokesperson for 5 Live said, “This is shameless paid-for lobbying. Given this report was paid for by the parent company of TalkSport, people can judge its credibility for themselves.”

The BBC was not challenging the report’s methodology, instead it was saying that research by a team of academics at a respected University should be ignored because it had been paid for. There is something troubling about the BBC’s remarks. For a start there’s the tone of moral superiority. Then there’s the defamatory innuendo that critics of the BBC are mere hirelings serving the squalid interests of commerce. Putting these objections to one side, what is wrong, one is entitled to ask, with research which has been commissioned, or funded by a research grant?

The BBC frequently pays organisations to carry out audience research. For example, in 2016 the BBC commissioned the company ICM Unlimited to carry out a Purpose Remit Survey to measure how well the corporation delivered its “six public purposes”. The report was largely positive. It announced that, “Four in five (78%) would miss the BBC if it were no longer there”, and “The proportion of the public holding a favourable impression of the BBC (58%) has increased since 2015.” Does the BBC think its Purpose Remit Survey should be dismissed as “shameless paid-for lobbying?” Presumably not. Did News UK issue a press statement impugning the integrity of the ICM researchers? No they did not.

Surely the right way to think of the University of Kent researchers, and the ICM researchers, is as expert witnesses. The purpose of expert witnesses in judicial proceedings is to give independent, expert opinion to help the court decide where truth lies. But expert witnesses are not expected to compile their reports gratis. Their fees are paid by the side which instructs them. The whole point about expert witnesses is that they have expertise which others lack. Their knowledge, skill and experience can be used to gather and interpret factual evidence. In this case the University of Kent’s funders were undoubtedly pleased with the results, and the BBC displeased. But instructing a team of reputable academics to scrutinise the behaviour of a publicly funded body is entirely reasonable. Indeed in a democracy it is essential. Luckhurst et al state their methodology, present their data and explain their conclusions. That’s exactly what academics, and journalists, are supposed to do.

This is an extract from Graham’s article in the British Journalism Review. Volume 30, Number 1, 2019